System Change: A Basic Primer to the Solidarity Economy

Posted by Collectivist

"The Covid-19 pandemic has upended our world. It has laid bare the inequity, the limits, and the failures of capitalism. The door to a better future beyond capitalism, already cracked open by the Great Recession, has been pushed open a little wider.

"The Covid-19 pandemic has upended our world. It has laid bare the inequity, the limits, and the failures of capitalism. The door to a better future beyond capitalism, already cracked open by the Great Recession, has been pushed open a little wider.

Things that seemed impossible a few months ago now seem both possible and necessary. This historic moment calls for us to push hard and through that door to build a world that centers people and planet. To do so, we need to be clear about what we’re trying to leave behind (capitalism) to have greater clarity about what it is that we’re moving towards (post-capitalism and solidarity economy).

Alternatives to capitalism are gaining adherents. Indeed, a recent Gallup poll found 43 percent of the respondents expressing support for socialism propelled by the candidacy of Bernie Sanders and his platform of democratic socialism.

And yet, there is a great deal of confusion about both what socialism and capitalism mean. Here we look at different systems or models of socialism, capitalism, and solidarity economy.

For those working for system change, clarity is imperative. In its absence, the default is likely to be to “reform” capitalism, without even considering the possibility of building an economy and world beyond it. We respect those who seek a just and sustainable world by reforming capitalism. We just disagree as to whether that is possible.

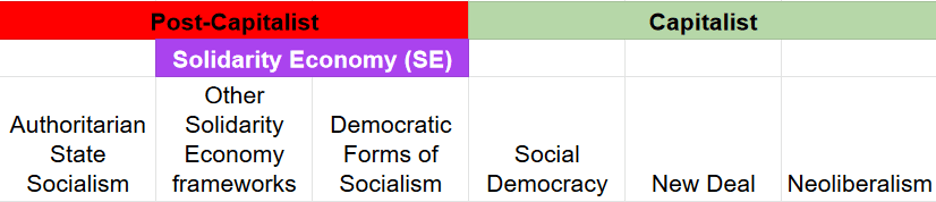

Table 1 provides a framework that distinguishes capitalism and post-capitalism. It identifies the main modern capitalist and post-capitalist economic systems, which we discuss below. Within post-capitalist systems, the solidarity economy, as detailed below, does not include undemocratic systems such as authoritarian state socialism.

Table 1

But What Do We Mean by Capitalism, Anyway?

It is all too common for people to say that capitalism is so complex that it cannot be defined. This is not true. Here is a simple definition of capitalism, one used by the Center for Popular Economics, a collective of progressive/radical economists that seeks to demystify how the economy works (or doesn’t work), that has stood the test of time for over 40 years.

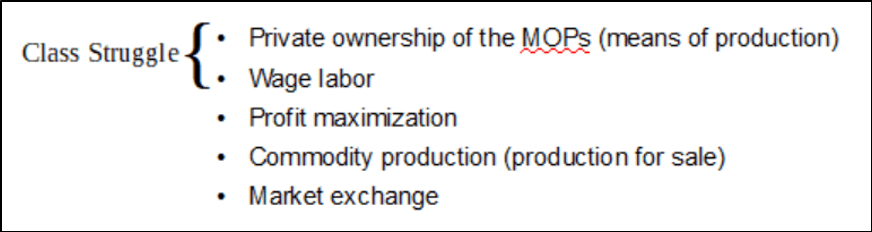

These are the five interrelated characteristics that define capitalism:

One characteristic alone does not make an economy capitalist. For example, markets pre-date capitalism by thousands of years and can also exist in socialism. The same goes for commodity production—production for sale, rather than use.

The specificity of capitalism’s mode of production lies in its division between owners (capitalists) of the means of production (land, buildings, machinery, tools, etc.) and the workers who produce goods and services. Capitalists maximize profits in many ways, but often by squeezing the workers—and therein lies the class struggle. A worker-owned co-op may produce commodities for sale in the market, but it is not a capitalist enterprise because the workers are the owners, thereby eliminating the class divide.

There is, of course, much more that can be said about capitalism—about its tendency to concentrate wealth and power, to celebrate the pursuit of self-interest as a social virtue, about its tendencies toward crises, about its incessant drive for growth.

Further, note that this definition of capitalism focuses on class. But capitalist economies in the real world intersect with other forms of domination, producing and reproducing gender, race, and man/nature inequality and exploitation, as well as class.

Types of Capitalism

There isn’t just one capitalist system. Table 1 above identifies three models: neoliberalism, New Deal capitalism, and social democracy. These are positioned along a spectrum, where the right represents free market, small government, competitive forms of capitalism, and the left represents an active government that provides regulations and redistribution to protect people and planet, including feminist, anti-racist, and ecological principles and policies.

Neoliberalism, currently the dominant economic paradigm in the US and much of the world, broadly asserts a vision of government small enough to “drown in a bathtub,” as Grover Norquist put it. Of course, that is hardly likely to happen, but neoliberalism as an ideology has been used to promote austerity (i.e., reduced education, health, and social spending), pro-corporate regulation and privatization; shift taxes from the one percent to working people; and increase police and military spending (an item requiring a larger state). This is all done in the name of maintaining “free” markets, ignoring the fact that these markets are constructed by the state to favor owners of capital and are far from free.

Prior to neoliberalism, capitalism was dominated by New Deal capitalism (sometimes referred to as Keynesianism) in which government sought to build a social safety net, address market failures, regulate unscrupulous businesses, bust up monopolies, and at least nominally promote greater economic equality.

New Deal capitalism emerged from the utter failure of President Herbert Hoover’s policy approach to the Great Depression of 1929. Year after year the Depression deepened, until the Roosevelt administration began in 1933 to push through the New Deal (stolen from Eugene Debs and the Socialist Party), which, in addition to establishing social security, unemployment insurance, antitrust measures, union rights, and much more, created large-scale public programs such as the Works Progress Administration. These measures started to pull the economy out of the Depression, but it took the even more massive public spending of WWII to finally boost the economy back to full employment and rapid economic growth.

New Deal capitalism continued into the 1970s. However, billionaires and other conservative forces gradually undermined it. A paradigm shift occurred such that neoliberalism became the dominant discourse, and tax cuts for the wealthy (and, less spoken about, tax increases for working people) became the norm. In recent years, however, New Deal capitalism may be making a comeback, with many seeing Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign in 2016 as initiating a snowballing movement back toward a New Deal-like paradigm.

Social democracy, as epitomized by Scandinavian economies, is a stronger and more generous version of New Deal capitalism (or perhaps Scandinavians would say that the New Deal was watered-down social democracy). While social democracy can serve as a transitional phase toward post-capitalism, it is still capitalist, as capitalist corporations continue to dominate the economic and political landscape.

It is important to note that whichever economic paradigm is dominant, there are always elements of other systems that exist. So, within neoliberal capitalism, there also can exist elements of pre-capitalism (e.g., human trafficking, which is a form of slavery) and post-capitalism (e.g., worker cooperatives).

What does “post-capitalism” look like?

Having defined capitalism, what then is post-capitalism? It literally means “after capitalism.” A post-capitalist framework holds that no matter how we “tame” or “humanize” capitalism, its fundamental logic precludes living in harmony with each other and nature. Capitalism’s development has been inextricably intertwined with racism and patriarchy and continues to exploit both. Capitalism’s drive to “accumulate or die” drives insatiable extraction from nature. Post-capitalism attempts to build upon capitalism’s achievements while transforming and transcending its obvious failures. . ."

Comments

Post a Comment